Demand for analog semiconductors is surging as waves of digital applications ripple through all segments of the world economy.

Demand for analog semiconductors is surging as waves of digital applications ripple through all segments of the world economy.

After about two years of tight supply conditions with severe shortages of critical components across the electronics manufacturing industry, electronic manufacturers, Tier-1 vendors and semiconductor suppliers are confronting a new dilemma: figuring out the optimal level of components to keep in stock as economists predict a softening of demand across the globe.

Current projections call for semiconductor sales to remain strong for at least the next couple of years and the long-term trendline points towards solid demand due to the growing injection of chips into various parts of the economy. But with signs consumer demand is flagging and as economic regulators take steps to tamp down on inflation, chipmakers may struggle to determine optimal inventory levels, intensifying the current demand-supply imbalance, according to analysts and industry executives.

“The semiconductor industry had an extremely strong growth year in 2021, but shortages and tight inventory in some semiconductor markets remain,” said Nina Turner, research manager, Semiconductors at IDC, in a report. “Longer term, the new fabs and investment announcements will add significant capacity and could increase the risk of overcapacity beyond 2023.”

Supply conditions remain challenging now with lead times still stretching out months for components used by car OEMs and PC makers, but industry executives say they are similarly bracing for a slowdown based on a downward revision of economic growth rates by forecasters. In such a situation, the demand-supply dynamics could swiftly change, resulting in spot overages for components, they said. Veterans of the electronics supply chain said the growing uncertainties about future demand will only increase tension in the supply chain. One resolution is for OEMs and their supply chain partners to increase their collaboration and improve visibility into demand and inventory stocks.

“The industry is looking at building the safe level of inventory although we think this should be in 2023 when the supply chain becomes normalized,” said Marco Monti, president of STMicroelectronics’ automotive and discrete group, in an interview. “The current shortage is demonstrating that the supply chain as of 2020 was not able to prepare the right [inventory] capacity for today.”

Determining the future direction of electronics demand has always been problematic for the industry. Forecasts often either fall far short of actual demand or overshoot, leading to a mismatch in demand-supply planning at OEMs. But as OEMs and semiconductor suppliers have just begun working more closely together to improve planning, economists are sending a different signal about the global economy. Driven by complications from the war in Ukraine, continuing negative impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns, rising inflation, higher energy prices and a spike in commodity costs, the World Bank is now predicting “feeble” growth in economic activities.

In a report released early in June, the global organization said it had revised downward its forecast for 2022 economic expansion and now sees growth averaging 2.9 percent, versus 5.7 percent in 2021. Per capita income “in developing economics this year will be nearly 5 percent below its pre-pandemic trend,” the World Bank said in its press statement. This implies lower available income for buyers, which will affect all sectors of the economy. For developed economies, the World Bank now expects a deceleration in economic activities. The Bank shaved 1.2 percentage points from its earlier forecast for developed economies and now sees the group of countries advancing only 2.6 percent this year, down from 5.1 percent in 2021.

“Just over two years after COVID-19 caused the deepest global recession since World War II, the world economy is again in danger. This time it is facing high inflation and slow growth at the same time,” said World Bank president David Malpass, in the organization’s Global Economic Prospects report. Even if a global recession is averted, the pain of stagflation could persist for several years — unless major supply increases are set in motion.”

Not primed for a slowdown

A slowdown in the global economy will have implications for the electronics industry and its supply chain. Currently, executives are in general planning for continued economic expansion and tight supply conditions rather than a slowdown in demand. In fact, many companies across the electronics supply chain are more focused on rebalancing the supply chain by ensuring availability of components. Tales continue to echo through the industry of delayed orders and production slowdowns or shutdowns due to the non-availability of components.

This is happening especially in the automotive industry where semiconductor suppliers are struggling to fulfil demand for a range of components. Lead times for parts are stretched out for months and some vehicles are still being shipped without the full assortment of non-safety features such as power HVAC controls, cruise systems and USB ports. Ford, for example, told dealers that some buyers would have to wait up to one year to have rear HVAC controls because the automaker was unable to secure chips for the features. Tesla, Cadillac and BMW were also impacted by the semiconductor shortage which forced them to ship cars without touchscreens, for instance.

“Today, there is no excess inventory or sufficient inventory [of semiconductors] at carmakers, Tier-1 suppliers and semiconductor suppliers; we are still in a situation of extreme shortage,” said ST’s Monti. “This has shifted control of the supply chain to OEMs, and we are welcoming this because we have more clarity about demand.”

But demand is already slowing, and the shortages are easing even if it has not yet shown up in company income statements. In fact, a few executives are warning of a looming slowdown and taking steps to insulate their operations. Tesla, for example, plans to reduce its workforce by 10 percent and is freezing hirings. CEO Elon Musk asked his managers to take these steps because he had a “super bad feeling” about the economy. Tesla is a major consumer of semiconductors and if the sales of its electric vehicles were to stall this could negatively impact many of its suppliers.

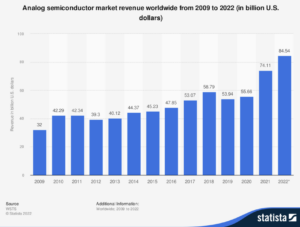

Enterprise growth forecasts are reflecting the slowdown. After several years of torrid growth, research firms and electronic manufacturers are guiding for slower expansion. Semiconductor sales in 2022, for example, are projected to remain strong but ease back to 16.3 percent from 26.2 percent in 2021. By 2023, though, the market is forecast to grow only 5.1 percent, according to the World Semiconductor Trade Statistics, (WSTS), an industry body.

“WSTS forecasts strong chip demand for another consecutive year, with most major categories expected to see high teens year-over-year growth in 2022, led by logic with 20.8 percent growth, analog with 19.2 percent growth, and memory with 18.7 percent growth,” the organization said, in a statement. “Optoelectronics remains the weakest category in the forecast and is expected to be roughly flat (+0.3 percent) year over year.”

The industry has taken steps to counter the shortages experienced in the last year. Manufacturing fabs are operating near or at full capacity while plans to build new plants have been accelerated, in cases with the promise of assistance from governments. These new plants will only become operational in the next two years when demand may have eased, according to observers. Further complicating the supply chain challenges companies will face as they transition from a high-growth to a moderate-growth environment is the likelihood that some OEMs and EMS providers may have piled up excess inventories during the current shortage crisis. Semiconductor suppliers may have little to no visibility into the excess stocks, which could hurt their stock planning if buyers cut back on future orders, according to analysts at Deloitte.

They recommend the following actions:

A. Better lead-time management: “12-weeks is about average, so moving towards that level is a key goal before the end of the year.”

B. Monitor inventory levels at customers and distributors: “As a result of the shortage, some customers may be hoarding or at least over-ordering. Once the shortage resolves, they could start working down excess inventories, leading to abruptly decreased demand.”

C. Government may not deliver on promised support: “Semi companies should be on the alert for flagging support, as well as cancelled or abandoned incentives.”

D. Wage inflation pressure: “The ongoing talent war continues to see companies struggle to fill positions. Compensation has not risen materially; however, as the competition for talent intensifies, that could change.”

E. Capex cutback may be inevitable: “Current [capex] run rates are over $100 billion annually, and as the industry shifts into balance, stakeholders may start arguing for a reduction.”

F. Watch for threat of global disruptions: “Significant global/regional political, trade, or conflict events … could yet again radically alter chip companies’ strategies and business models.”