Semiconductor sales are weakening amidst efforts by governments to tame spiking inflation. Are these the early signs of another downturn and how should chipmakers prepare for another one of its notorious downcycles?

Semiconductor vendors, chip equipment makers and their OEM and EMS provider customers were still trying to make sense of a crippling supply chain crisis when an old nemesis suddenly showed up at the tail end of the second quarter. Inventories are rising again and quicker than expected raising the specter of another one of the semiconductor market’s erratic boom and bust cycles.

Veterans who went through previous cycles, especially the horrid excess inventory-driven downcycle from 2001, are trying to raise the alarms but the signs are not definitive yet. Memory manufacturers are pointing to weakening demand from the PC and consumer electronics segments, rising inflation and supply chain pressures from the Russia-Ukraine war have compounded concerns about the direction of the global economy. In addition, continuing shortages of some critical semiconductor components have forced design changes at many OEMs, some of which have similarly altered their production schedules.

“Across the industry, there are cost challenges stemming from supply chain and inflationary pressures. We are seeing some enterprise OEM customers wanting to pare back their memory and storage inventory due to non-memory component shortages and macroeconomic concerns,” said Sanjay Mehrotra, CEO of Micron Technology, during a presentation to financial analysts. “A number of factors have impacted consumer PC demand in various geographies. As a consequence, our forecast for calendar 2022 PC unit sales is now expected to decline by nearly 10 per cent year-over-year from the very strong unit sales in calendar 2021. This compares to an industry and customer forecast of roughly flat calendar 2022 PC unit sales at the start of this calendar year.”

A storm is brewing in the economy with ominous implications for technology manufacturers and especially chip vendors who have notched explosive growth in the last couple of years. Data from developing and developed economies are not positive, pointing to a steady erosion of consumer confidence as high energy costs and rising interest rates crimp personal and corporate purchasing power. As a result, forecasters are paring back their economic projections.

The World Bank has shaved several percentage points off its earlier projection and now sees the world economy expanding only 2.9 per cent in 2022 versus its earlier estimate of 5.7 per cent. Many countries may find it difficult to avoid a recession, which could hurt demand for semiconductors.

“Amid the war in Ukraine, surging inflation, and rising interest rates, global economic growth is expected to slump in 2022,” said David Malpass, president of the World Bank Group, in a report. “Several years of above-average growth are now likely, with potentially destabilizing consequences for low- and middle-income economies.”

Could the semiconductor market be different? Despite signs of a looming weakness in some segments, overall semiconductor demand remains strong, according to observers. In fact, it is still stubbornly difficult to get chips for certain OEM products, including components for automotive, data and connectivity devices, communication, and networking equipment. Extended lead-times are still the norm for automakers, many of which still get supplier delivery schedules extending out six months or more for critical components. The cost of the shortages to manufacturers and the extended food chain is enormous, according to analysts at research and consulting firm Deloitte.

“Chips will be even more important across all industries, driven by increasing semiconductor content in everything from cars to appliances to factories, in addition to the usual suspects—computers, data centers, and phones,” said Deloitte analysts in a report jointly authored by John Ciacchella, Brandon Kulik, Dan Hamling and Chris Richard. “Across multiple end markets, the absence of a single critical chip, often costing less than a dollar, can prevent the sale of a device worth tens of thousands of dollars. Based on our analysis, the chip shortage of the past two years resulted in revenue misses of more than $500 billion worldwide between the semiconductor and its customer industries, with lost auto sales of more than US$210 billion in 2021 alone.”

While some forecasters have similarly reduced their growth estimates for the industry, they see pockets of strength that they believe could help the industry better navigate the building storm. Also, digitalization programs at enterprises have dramatically expanded areas of the economy that now use semiconductors, turning chips into the essential lubricant for productivity gains in areas as diverse as agriculture, automotive—think EVs and Avs—aviation, communication, industrial, medical, security and transportation.

“More and more products have at least some chips integrated into their design every year, and more and more products have more chips than they used to, from connected devices in our homes to smart tags on every box in a warehouse,” Deloitte said. “That’s not all; chips are also rising in their value and capabilities. For example, the semi content per car will roughly double between 2013 and 2030.”

That is the good news. Other data point towards a hard landing for chipmakers in line with the rest of the economy. Micron was not the only company warning of a slowdown. Intel Corp. is similarly concerned about what its executives described as a “noisier” sales environment, causing it to freeze hiring in June, according to reports. Nvidia, too, is reducing hiring in response to a slowing demand environment, sources said. Auto OEM Tesla has also begun actions to reduce costs although CEO Elon Musk only cited his concerns about the direction of the global economy.

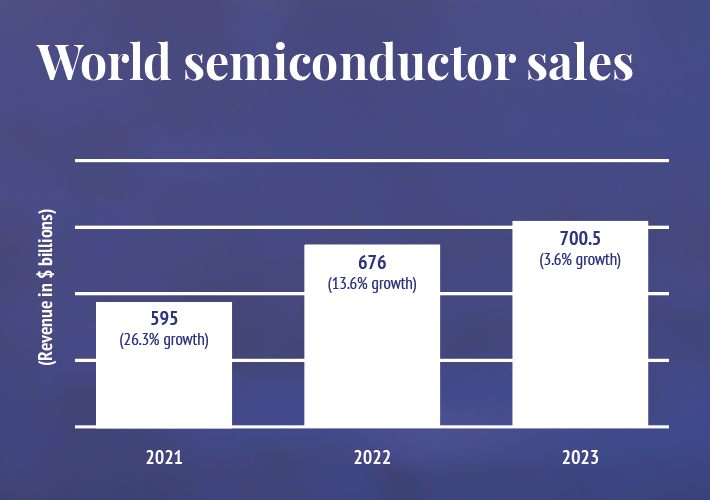

These actions are typical steps companies take when they see dark clouds gathering on the horizon. The semiconductor market is not different. For one thing, nobody should expect the kind of giddy growth that semiconductor manufacturers recorded in 2021 when total industry revenue rocketed up 26 per cent, to $556 billion according to the World Semiconductor Trade Statistics, (WSTS). The industry association sees strong but less robust growth in 2022. Its latest forecast was for an increase of 16 per cent in semiconductor sales for 2022, rising to $646 billion.

Forecasters are predicting slower growth in the region of 10 per cent, however. The shortages that drove the 2021 and first-half 2022 market expansion are easing steadily, they said, adding that inflationary pressures will further stifle consumer demand. Chip capacity utilization rates have also been pushed up and additional manufacturing fabs will come online in the next several years, further easing the choking supply chain shortages.

The market will get better visibility by the end of the third quarter. By then, end-of-year orders would have been fully processed, providing insight into consumption patterns as well as first quarter demand. Additionally, the ongoing liquidation of inventories built up since the beginning of the year as a hedge against supply shortages would be in full throttle, adding to end-demand visibility.

What should the industry do to return the supply chain as close as possible to a semblance of equilibrium? First, the extensive communications and exchange of demand-supply information between semiconductor vendors and customers should be maintained and reinforced. The greater the amount of information exchanged by the parties involved the better the visibility into market conditions, which would enhance forecast accuracy.

Semiconductor suppliers will tamp down on production to eliminate any swollen inventory pockets and reduce the adverse impact on average selling prices and the profit gains they have accumulated through the shortages. Micron hinted at this strategy in its recent analysts’ presentation, noting that the memory supplier expects to reduce DRAM bit supply growth in the second half of this year and beyond.

“Given the market conditions, we are taking immediate action to reduce our supply growth trajectory,” Mehrotra said. “To maintain profitability, we will maintain pricing discipline, manage capacity utilization, and use inventory as a buffer to navigate through this period of demand weakness. We will continue to exercise supply discipline and take appropriate actions to navigate through the near-term headwinds.”